New York City's Complicated Relationship with Captive Audience Meetings

New York, NY.

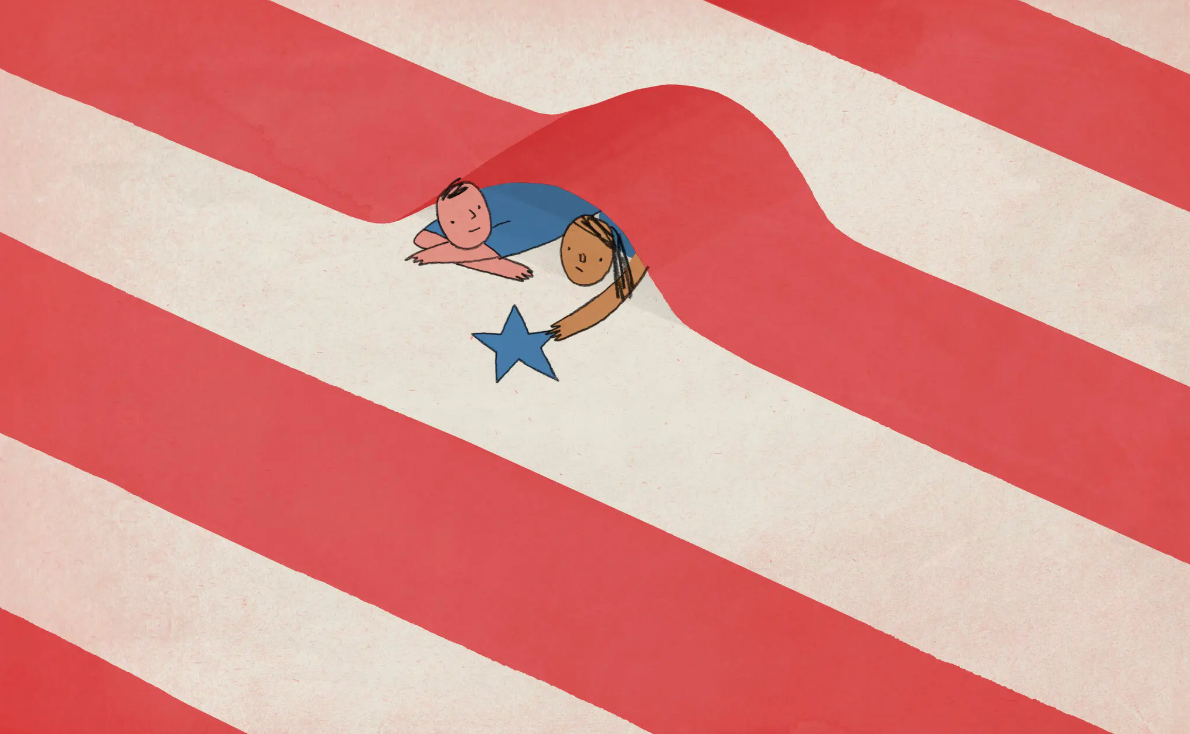

In 2021, amid post-election frenzy, the New York City Labor Law was passed, banning captive audience meetings.

Introduction

Captive audience meetings, mandatory convenings where an employer subjects their opinions on unionization to sway employee opinions on politics, remains a significant issue, one that is now illegal through the New York City Labor Law Act of 2021. The meetings are often employed by businesses, including large national chains such as Darden restaurants (detailed later in the brief), to influence workers’ views on union activities and labor policy, often undermining workers’ rights to make independent choices regarding collective bargaining. Despite federal protections under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935 that guarantee workers the right to unionize without interference, meetings requiring employees to attend these meetings are controversial. While some argue that captive audience meetings are a legitimate form of free speech, others argue that they serve as coercive tools that undermine workers' basic rights to organize freely.

The legal question hinges on whether these meetings constitute undue pressure on employees, particularly in states like New York, where labor protections are more robust. This policy brief focuses on the legal framework governing captive audience meetings in New York City in particular, drawing on specific case studies—particularly the high-profile case involving Darden Restaurants, the parent company of Olive Garden and LongHorn Steakhouse—to examine the practical and legal ramifications of the practice. Through detailed analysis of legislative developments, court rulings, and industry-specific examples, this brief recommends a reevaluation of current protections to ensure that employees are afforded the ability to make free and informed decisions about unionization and politics.

Constitutional Dimensions and First Amendment Complexities

At the heart of the debate over captive audience meetings lies the tension between the First Amendment's protection of employer speech and employees' rights to free association without coercion. While NLRB v. Gissel Packing Co. (1969) established that employer speech is protected on the grounds that it doesn’t contain threats or promises, it failed to address whether mandatory attendance itself constitutes an inherent coercion, and the nature of the topics discussed that would deem it illegal or legal activity. Critics argue that requiring attendance in a hierarchical workplace inherently blurs the line between protected speech and undue influence, particularly given the power dynamics at play.

Furthermore, compelling employees to participate in such meetings may constitute a form of compelled speech under Janus v. AFSCME (2018), where the Court ruled that workers cannot be forced to subsidize union activities with which they disagree. Extending this logic, it could be argued that captive audience meetings compel employees to engage with political speech they may oppose, thus infringing on their First Amendment rights. Courts have yet to squarely address this potential conflict in the application of First Amendment rights, but future litigation may present an opportunity to redefine the boundaries of free speech in employer-employee relationships.

Legal Status of Captive Audience Meetings

Under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), employees have the right to engage in concerted activities, which includes the formation of unions. However, Section 8(c) allows employers to express their opinions about unionization, as long as they do not coerce employees' rights to organize or interfere with their organizing. Captive audience meetings, by their nature, exist in a gray area: they allow employers to express views while demanding workers' attendance, raising concerns over whether these meetings truly remain voluntary. Captive audience meetings that require employees to leave their workplace–in some cases, to local legislation in seeming support of the employer’s cause–are often most controversial. In New York, where labor protections tend to be stronger relative to other states, the fine line is even more pronounced. Local statutes and judicial rulings have sought to balance employer speech with employee rights, creating a complex legal landscape.

Captive audience meetings became effectively illegal in New York City following the passage of the New York City Labor Law in 2021, which introduced specific protections for workers, particularly aimed at curbing coercive employer tactics during unionization campaigns and reinforcing Section 8(b) of the NLRA . This law was part of a broader set of labor reforms in the city designed to strengthen workers' rights and address unfair practices by employers. Under the law, employers are prohibited from requiring employees to attend any meetings or events where unionization activities are discussed, specifically mandatory meetings in which employers attempt to dissuade employees from joining a union. The law goes beyond addressing union meetings, and applies to situations where the employer might engage in similar tactics through other forms of communication or gatherings, such as one-on-one meetings or group discussions on politics.

The legal rationale behind this shift stems from concerns over employee autonomy and the undue pressure that mandatory attendance at such meetings places on workers (and risk of job loss if absent), effectively restricting their freedom to make independent decisions regarding unionization. Critics argued that forcing employees to attend anti-union meetings created an unfair power dynamic, especially when employees feared retaliation for not complying. Legal scholars and labor rights advocates pointed to the inherent conflict of interest in requiring workers to attend meetings where they were pressured to align with the employer’s position.

Benjamin Sachs, a Kestnbaum Professor of Labor and Industry at Harvard Law School, noted “Mandating that employees attend a meeting, and backing that mandate with the threat of discipline or discharge, is simply not noncoercive speech; indeed, it is neither noncoercive nor speech.” NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo argues that the current framework allowing coercive tactics in employer-employee relations constitutes a significant deviation from the foundational principles of the NLR) in critique of recent labor law interpretations. As she states: “This license to coerce is an anomaly in labor law, inconsistent with the Act’s protection of employees’ free choice. It is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of employers’ speech rights.”

Legal challenges to captive audience meetings have grown over the years, particularly with the shift towards more robust worker protection laws at the state and local levels. The California Labor Code, for example, has also been cited as a model for strengthening protections against such employer-driven tactics, including regulations that restrict the use of mandatory anti-union meetings.

An increasing body of research and legal precedents illustrating the harmful effects such meetings have on the autonomy of employees informed New York City's ban on captive audience meetings. A 2018 report by the Economic Policy Institute found that mandatory anti-union meetings exert significant subconscious pressure on employees to conform to their employer’s anti-union stance. These meetings not only reduce workers' freedom of choice but also contribute to a chilling effect on union support, as employees are less likely to express their views openly for fear of retaliation. The American Bar Association has also weighed in, arguing that captive audience meetings violate fundamental principles of free speech by coercively directing workers' attention toward one side of the issue in a workplace context where their personal beliefs and rights should take precedence.

Additionally, the advent of New York City's law has sparked significant discussions about the effectiveness of such prohibitions and the potential for national-level reforms. The success of the New York City law is being closely monitored by labor activists and policymakers nationwide, particularly in light of ongoing efforts to reform the National Labor Relations Board’s stance on captive audience meetings.

Recent litigation in California over legislation regulating captive audience meetings highlights a critical tension in labor law and constitutional rights, as employers challenge restrictions on mandatory political and anti-union meetings. These laws, designed to protect employees from coercion, have faced First Amendment challenges from corporations arguing that such regulations unconstitutionally restrict their right to free speech and ability to communicate critical business information.

Plaintiffs contend that these laws are overly broad, impeding voluntary, non-coercive interactions and potentially undermining organizational loyalty and transparency. Labor advocates counter that these protections are essential to safeguarding employees’ rights to free association and preventing workplace intimidation, particularly in the context of unionization efforts.

The California lawsuits, which remain unresolved, serve as a key test for how courts balance the competing interests of employer autonomy and worker protections. The outcomes may significantly influence legislative approaches in New York and beyond, setting precedents for how far states can regulate workplace communications without infringing on constitutional freedoms, while shaping the broader discourse on corporate influence and collective bargaining rights.

The Case of Darden Restaurants

Darden Restaurants, the parent company of well-known chains such as Olive Garden and LongHorn Steakhouse, provides a clear illustration of how captive audience meetings play out in practice and the legal ramifications they entail. In 2015, employees at a Darden restaurant in New York City attempted to organize a union to improve working conditions and wages. In response, management conducted a series of captive audience meetings, in which they presented anti-union arguments to employees. While Darden argued that the meetings were within their rights to express their opinions, employees and labor advocates contended that these meetings were coercive, particularly given that attendance was technically mandatory and employees felt pressured to comply.

The legal proceedings following the incidents brought the practice of captive audience meetings into sharper focus. In 2016, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) issued a ruling on the case, determining that while employers had the right to express their views on unionization, mandatory attendance at anti-union meetings created a coercive atmosphere, especially when linked to threats of retaliation. Although the NLRB did not completely ban the practice, it required more stringent guidelines to ensure that such meetings did not infringe upon workers’ rights to organize. The case set a precedent for how the NLRA and local laws should interact to protect workers from undue influence during unionizing efforts.

However, the case took on new dimensions when Darden was accused of using retaliatory tactics against workers involved in the unionization effort, including reassigning them to less favorable positions and engaging in surveillance of their activities. This led to further legal challenges and scrutiny of the company’s practices. In 2017, the New York City Department of Labor issued a public statement condemning the use of captive audience meetings in union-related disputes, emphasizing that such tactics violated the spirit of local labor laws designed to protect workers from employer coercion. The city’s stance highlighted a significant divergence between federal and local legal interpretations of employer conduct in the context of unionization.

The Darden case illustrates how captive audience meetings, while legally permissible in many circumstances, can cross into problematic territory when employers leverage their power over workers to influence union outcomes. The case also underscores the challenges workers face when combating coercive tactics, especially in large, corporate environments where management holds significant influence.

The Case of Walmart

Walmart, one of the largest retail chains in the United States, has been involved in legal battles regarding captive audience meetings, particularly in California, where similar laws banning such meetings have been in place for years. While New York City has only recently enacted its own legislation, California’s long standing restrictions offer valuable insight into how large corporations may respond to similar laws in New York.

In 2020, Walmart faced legal challenges after being accused of violating California’s law prohibiting captive audience meetings. The case was brought to light after workers alleged that they were forced to participate in meetings where management discouraged unionization efforts. Walmart subsequently defended its actions by claiming that these meetings were not intended to infringe on employee rights but were rather part of an overall company-wide effort to communicate corporate policies and foster a positive work environment.

Walmart’s legal defense hinged on the argument that its First Amendment rights protected its ability to communicate freely with its employees, including presenting its views on unionization. The company argued that prohibiting these meetings would infringe upon its First Amendment rights, especially in a highly competitive and politically charged environment like retail. Walmart also argued that the law itself was nonspecific and would inhibit normal, everyday communications between managers and employees.

In Working for Respect: Community and Conflict at Walmart, sociologists Adam Reich and Peter Bearman explore the ways in which Walmart enforces its anti-union stance. The authors describe how Walmart creates a corporate culture that discourages unionization without the need for explicit bans or threats. Employees often experience pressure to conform to the company’s "family-like" atmosphere, where loyalty to the company is framed as a moral responsibility. This culture subtly reinforces the message that supporting unions is not just a business disagreement but a personal betrayal of the workplace culture. Workers are encouraged to see themselves as part of a team/family, which makes discussions of unionization feel out of place or disloyal to their colleagues.

Although Walmart’s challenge did not reach the state’s highest courts, it underscored a larger legal struggle between large corporations and labor advocates who argue for stronger protections for workers’ rights to freely associate, organize, and express their views without undue influence from employers. The case also highlighted a growing legal debate about the limits of corporate influence in the workplace and the scope of workers’ free speech rights.

In late 2021, Walmart agreed to implement new guidelines restricting mandatory meetings on political issues, including union-related topics, for a specified period of time. However, the company also maintained the right to hold informational meetings on workplace safety and other non-political topics, where employee participation remained voluntary. This settlement, though not a full-scale victory for labor advocates, represents a compromise between the conflicting interests of free speech and workers’ rights.

Walmart’s case in California reflects the broader trend of employers seeking to challenge or circumvent laws restricting captive audience meetings. As New York City continues to enforce similar regulations, it is possible that corporations in the city may adopt similar strategies in response to the new rules, including potential litigation or legal challenges aimed at modifying the scope of the restrictions. As these legal battles unfold, they will likely influence the future direction of captive audience meeting regulations, particularly in how far labor laws can go to regulate workplace communication without infringing on employers' constitutional rights.

Policy Recommendations

To ensure the effectiveness of New York City’s 2021 new ban of captive audience meetings, targeted policy interventions should address enforcement challenges, legal ambiguities, and clearer regulation on the dynamics of employer-employee relations. These recommendations aim to improve the law’s practical impact, reduce employer circumvention, and balance constitutional considerations.

1. Robust Enforcement Systems

One of the primary obstacles to effective implementation of the 2021 law is the lack of clear enforcement protocols to hold violators accountable, and most investigations are done privately by employee advocates. The city should establish an independent oversight body specifically tasked with investigating alleged violations of the law. The body would have the authority to conduct workplace audits, issue subpoenas, and charge substantial fines on non-compliant employers.

Additionally, the city could adopt a whistleblower protection system to encourage employees to report violations without fear of retaliation. Similar to the mechanisms in California’s Private Attorneys General Act (PAGA), workers could be empowered to file lawsuits on behalf of the city against employers who violate the law.

2. Clarification of Legal Parameters

A crux of the issue in regulating captive audience meetings lies in the legal gray area created by the intersection of the First Amendment and labor protections under the NLRA. To address this, the New York State Legislature should consider adopting explicit statutory language to define what the fine line is between constitutes coercion and violation of free speech in the context of mandatory meetings. In addition, the law should define the scope of "political" speech to include discussions not only on unionization but also on broader social and political issues that might indirectly affect workers’ organizing efforts.

3. Mandating Pre-Disclosure of Meetings

To prevent the coercive effects of surprise captive audience meetings, the city could require employers to provide prior written notice to employees detailing the purpose, agenda, and topics to be covered. Workers should also be informed of their right to decline participation without facing disciplinary action (the majority of workers are unaware of the new illegality of captive audience meetings). This procedural safeguard would ensure transparency while mitigating the perception of coercion inherent in unannounced mandatory meetings.

4. Adopting Technological Solutions for Monitoring Compliance to Regulations

Technology could be used as a checkpoint in identifying and addressing violations. The city could require employers to record all workplace meetings involving discussions of unionization or political topics, with the recordings made available for independent review in the event of a complaint. Employers could also be mandated to document attendance records and provide evidence that workers were informed of their right to opt out.

To increase accountability, the city could create a public compliance index that ranks employers based on adherence to labor laws. Such a system would incentivize compliance by leveraging reputational pressure while providing workers with transparent information about their current and potential employer’s labor practices.